DOI 10.18413/2312-3044-2017-4-2-156-173

SCYTHIAN COMPLEXES OF BARROWS 5 AND 6 FROM THE «GARDEN»

GROUP ON THE LEFT BANK OF THE LOWER DNIESTER

Vitalij S. Sinika,1,2 Sergei D. Lysenko,3 Nikolai P. Теlnov4

1 Scientific Laboratory “Archaeology,” T. G. Shevchenko Pridnestrovian State University

2 Scientific Laboratory of Historiography and Field Methods in Archaeology, Nizhnevartovsk State University

3 Department of Chalcolithic and Bronze Age, Institute of Archaeology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

4 Department of Ancient and Medieval Archaeology, Institute of Cultural Heritage, Academy of Sciences of Moldova

Abstract. Scythian culture represents one of the most intriguing archaeological phenomena of the early Iron Age in the northern Black Sea region. Burial monuments, or barrows, prevail among the archaeological evidence for Scythian material culture. Their excavation began more than two and a half centuries ago. There are currently more than 5,000 barrows that have been examined in this region.

The authors analyze the evidence obtained during the excavation of barrows 5 and 6 from the “Garden” group near the Glinoe village in the Slobodzeia district on the left bank of the Lower Dniester in 2017. Both complexes date from the late fourth to early third centuries BC. These barrows, as well as neighboring ones in this and other cemeteries, demonstrate not only Thracian and Greek influence on the material culture of Scythians of the northwestern Black Sea region, but also the fact that Scythian steppe culture developed continually in the Dniester region throughout the fourth to second centuries BC.

Keywords: Scythians, burials, Lower Dniester region, last quarter of the fourth century BC.

Copyright: © 2017 Sinika, Lysenko, Telnov. This is an open-access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source, the Tractus Aevorum journal, are credited.

Correspondence to: Vitalij S. Sinika, Scientific Laboratory “Archaeology”, T. G. Shevchenko Pridnestrovian State University. 3300, Tiraspol, 25 October st., 107, Moldova. E-mail: sinica80[at]mail.ru

УДК 903.53 “638” (478)

СКИФСКИЕ КОМПЛЕКСЫ КУРГАНОВ 5 И 6 ГРУППЫ «САД» НА

ЛЕВОБЕРЕЖЬЕ НИЖНЕГО ДНЕСТРА

Виталий С. Синика,1,2 Сергей Д. Лысенко,3 Николай П. Тельнов4

1 Научная лаборатория «Археология» Приднестровского государственного университета им. Т. Г. Шевченко

2 Научная лаборатория историографии и полевых методов в археологии Нижневартовского государственного университета

3 Отдел энеолита и бронзового века Института археологии Национальной академии наук Украины

4 Отдел античной и средневековой археологии Института культурного наследия Академии наук Молдовы

Аннотация. Скифская культура является одним из наиболее ярких археологических феноменов раннего железного века в Северном Причерноморье. Наиболее распространенными археологическими памятниками, которые дают информацию о материальной культуре скифов, являются погребальные памятники, а именно курганы. Их раскопки начались более 250 лет назад, и к настоящему времени в Северном Причерноморье исследовано более 5000 скифских погребений.

В данной работе представлены результаты раскопок двух скифских курганов – курганов 5 и 6 группы «Сад» у с. Глиное Слободзейского района на левобережье Нижнего Днестра, которые были исследованы в 2017 г. Оба комплекса датируются второй половиной IV – рубежом IV-III вв. до н.э. Данные курганы, как и соседние на этом и других могильниках, не только демонстрируют фракийское и греческое влияние на материальную культуру скифов Северо-Западного Причерноморья, но и то, что скифская степная культура в Поднестровье развивалась непрерывно на протяжении IV–II вв. до н.э.

Ключевые слова: скифы, погребения, Нижнее Поднестровье, последняя четверть IV в. до н.э.

In 2017 researchers from the Scientific Laboratory “Archaeology” of the Pridnestrovian State University investigated ten barrows near the Glinoe village in the Slobodzeia district on the left bank of the Lower Dniester. Among them, cemetery barrow 116 of the third to second centuries BC, which is situated on the northern outskirts of the village, has been excavated; its initial study started in 1995.[1] Research has been conducted on three barrows (6–8) in the “Sluiceway” group, which was excavated starting in 2015 (barrow 1) and continuing in 2016 (barrows 2–5).[2] A further six barrows (5–10) of the “Garden” group have been investigated; the first studies of this group were made in 2013 (barrow 1) and 2015 (barrows 2–4).[3]

This article represents the first publication of the results obtained during the research of the Scythian complexes of barrows 5 and 6 of the “Garden” group. These barrows are situated 2.8 km to the north-north-east of the outskirts of the Glinoe village. We first describe the funeral complexes and grave goods, and then provide our analysis.[4]

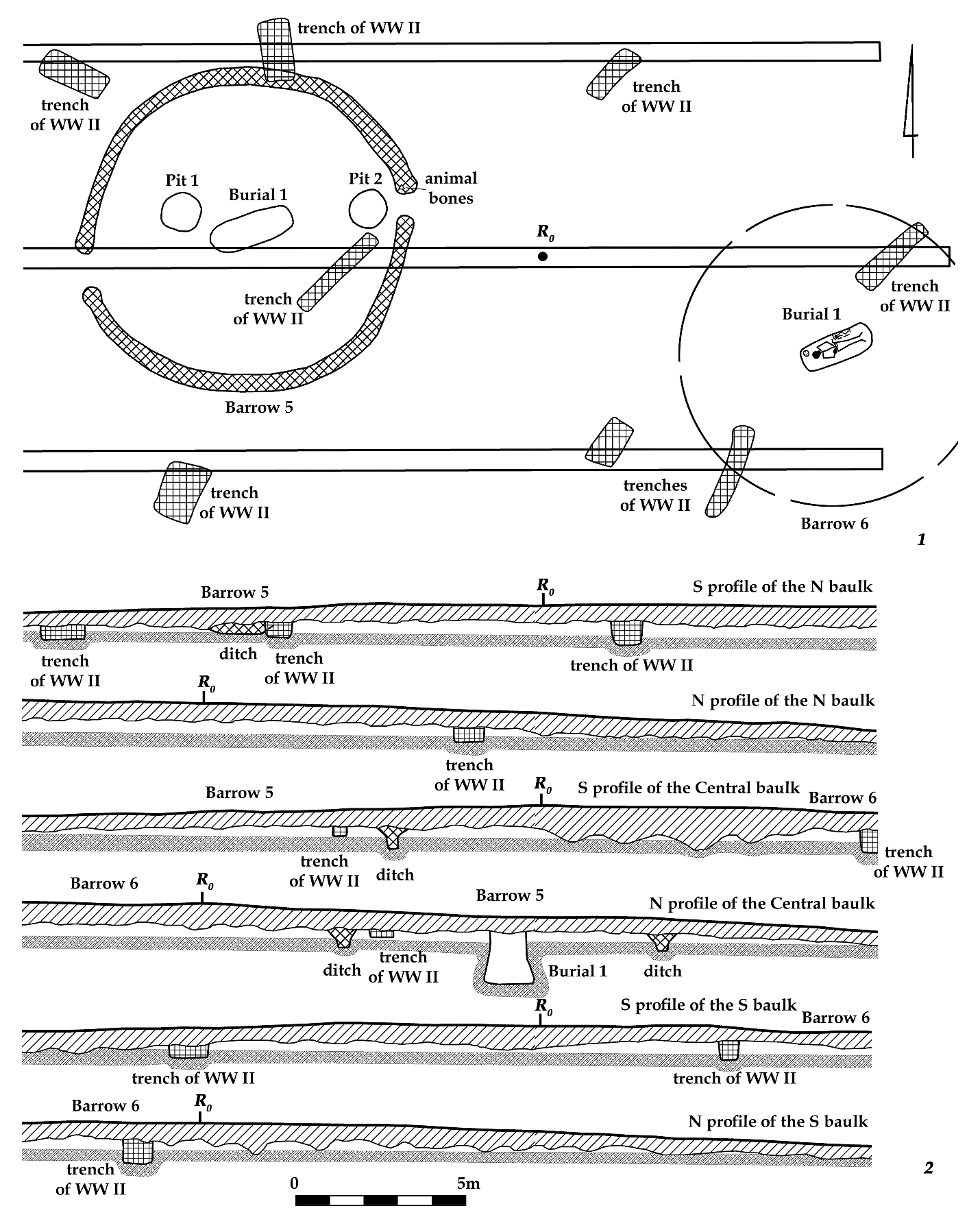

Barrow 5 was excavated in parallel trenches using heavy machinery. Three baulks were left in accordance with the line north-south with the width of 0.6 m. The length of the central baulk was 34 m; the length of the northern and the southern baulk was 30 m. The distance between baulks was 5.5 m (fig. 1: 1, 2). The mound was fully destroyed by plowing. This revealed a ditch, two ritual pits,[5] and a Scythian burial, which completely destroyed the main burial of the Early Bronze Age.

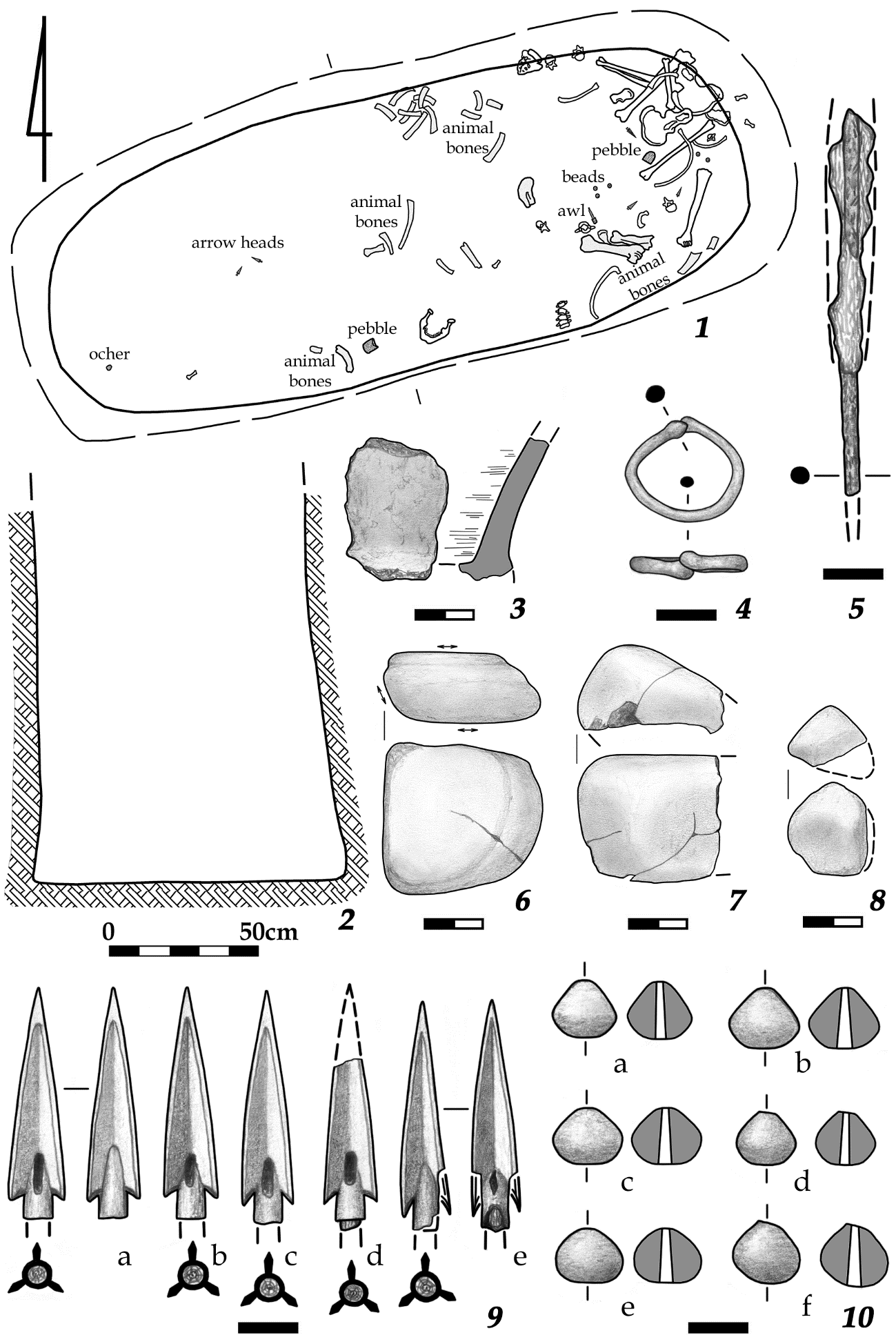

Burial 1 (Scythian, secondary) was found in the center of the barrow between the western and eastern breaks of the ditch on the same line. The grave was made in a pit. The contours of a rectangular pit with strongly rounded corners (with a length of 2.4 m and a width of 0.93 m) were detected at the depth of −0.97 m from R0. Due to the extension of the walls to the bottom of the pit oriented along the line west-south-west—east-north-east, the total size of the pit was 2.6×1.05 m. The bottom of the pit was fixed at the depth of −2.26 m from R0.

The burial was robbed in antiquity. There were adult human and animal bones from sacrificial food in the filling of the pit in disarray at different levels. Most of these bones were found in the eastern portion of the pit. A mandible lay near the southern wall (fig. 2: 1, 2). The pit contained the following additional items: three fragments of handmade pots,[6] five bronze arrowheads (2), a bronze ring (3), an iron awl with a horn handle (4), six glass beads (5), two pebbles (6) and a piece of ochre (7).

Description of the findings:

1. A fragment of the bottom part of a handmade pot. The base of the vessel is marked out by the tucks. The clay has admixtures of small chamotte and small micaceous sand. The external surface has yellow, grayish-yellow, and gray colors; the inside surface is black. The fragment’s size is 53×34 mm; the wall’s width is 7−8 mm (fig. 2: 3).

2. Five bronze trilobate arrowheads with protruding sleeves:

– the length of the arrowhead is 38.5 mm; the length of the sleeve is 11 mm, and the diameter is 5.5 mm. There is a 7×1.5 mm hole between vanes, which appeared as a result of a casting defect (fig. 2: 9a);

– the length of the arrowhead is 38.6 mm; the length of the sleeve is 13 mm, and the diameter is 5.5 mm. There is a 5.2×1.5 mm hole between vanes, which appeared as a result of a casting defect (fig. 2: 9b);

– the length of the arrowhead is 39 mm; the length of the sleeve is 13 mm, and the diameter is 5.2 mm. There is a 7.2×1.5 mm hole between vanes, which appeared as a result of a casting defect (fig. 2: 9c);

– the length of the arrowhead is 39 mm (the edge is broken); the length of the sleeve is 12 mm, and the diameter is 5 mm. There is a 5.2×2.1 mm hole between vanes, which appeared as a result of a casting defect (fig. 2: 9d);

– the length of the arrowhead is 38 mm; the length of the sleeve is 12 mm, and the diameter is 5 mm. There is a 3×1 mm hole between vanes, which appeared as a result of a casting defect (fig. 2: 9e).

3. A bronze earring with closed endings. The item is made from a circular rod. One of the endings is thickened and has a conical form; the other ending was broken in antiquity. The earring was probably used afterwards as a ring. The diameter of the ring is 19.6×17 mm. The diameter of the wire is 2×2.5 m. The size of the ending’s sections is 3.5×3 and 2.7×2.3 mm (fig. 2: 4).

4. An iron awl with a horn handle is partially preserved. The length of the preserved part is 64 mm; the diameter of the rod is about 3 mm. The length of the handle is about 45 mm; the diameter is greater than 9 mm (fig. 2: 5).

5. Six glass beads have asymmetrical biconical (fig. 2: 10a-d) and asymmetrical spherical (fig. 2: 10e, f) shape. One of the beads is yellow (fig. 2: 10a); the last five ones are blue (fig. 2: 10b-f). The height of the beads is from 4.5 mm to 5.4 mm; the diameter is from 5.2 mm to 6 mm. The diameter of the openings in the beads is from 1 mm to 2 mm (fig. 2: 10).

6. Two pebbles with traces of fire:

– a pebble from light-gray shale is 53×52×24 mm and has cracks on the surface. The large planes and one of the butts are slightly polished. This indicates that the item was primarily used as an abrasive (fig. 2: 6);

– a fragment of pebble from light-gray shale is 48×43×27 mm and has cracks and soot on the surface (fig. 2: 7).

7. The piece of yellow ochre with traces of fire. The size of the preserved part is 32×28×17.5 mm (fig. 2: 8).

Barrow 6 was discovered while excavating trenches during the research of barrow 5. Judging by differences in the height of the central and southern baulks, its diameter was not more than 9.5 m. The mound was fully destroyed by plowing (fig. 1: 1, 2).

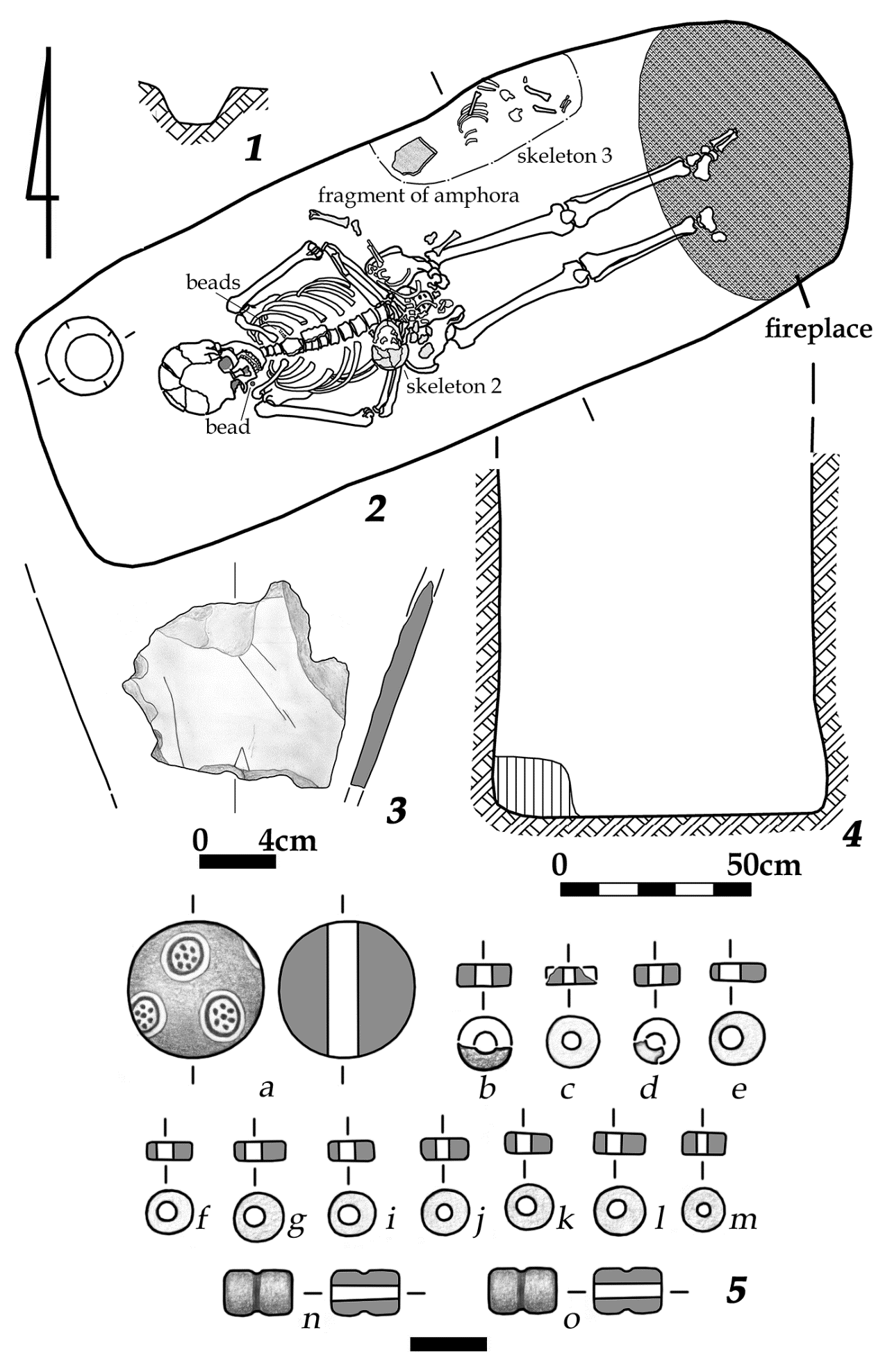

Burial 1 (Scythian, main) was discovered in the center of the barrow. It was done in a pit, above the eastern part of which was found a fireplace with a length of 0.8 m, a width of 0.55 m, and a depth of 0.4 m (between −0,6 m and −1 m from R0). Rectangular pit contours with strongly rounded eastern corners with a length of 2.25 m and a width of 0.82 m were fixed at the depth of −0.87 m from R0. The pit was oriented along the line west-south-west—east-north-east. The walls were straight. The bottom of the pit was noticeably uneven under the western and eastern parts at a depth of −1.65 and −1.68 m from R0, and at a depth of −1.76 m from R0 in the middle.

The remains of three individuals were found in the pit. Skeleton 1 (a woman) was lying in extended dorsal position; the head was oriented to the west-south-west. The arms were bent at the elbow and the hands were put on the pelvis; the legs were left straight. The necklace items (2) were found on the neck and the upper chest of the deceased. A bowl-like dimple (trapezium-shaped in section) with a diameter of 0.2 m in the upper part and 0.13 m in the lower part with a depth of 0.1 m was fixed to the left of the woman’s skull in the northwest corner of the pit. Skeleton 2 belonged to a little child, who was lying with the head to the south-south-west above the woman’s bones bent on the pelvis. We observed a peculiar “bed” near the northern wall of the pit to the left of the woman: an additional layer of natural clay with the admixture of humus with a length of 0.57 m, a width of 0.2 m, and the thickness of 0.15 m. On the “bed” there was a thin decay of albescent color from the organic mat where skeleton 3 was lying in a crouched position on the right side; it also belonged to a little child. His unpreserved skull was lying on the amphora's fragment (1), which lay on the western ending of the “bed” (fig. 3: 1, 2, 4).

Description of the findings:

1. A fragment of the wall of lower part of the orange-clay amphora of unrecognized producing center. The clay is an admixture of micaceous sand. The size of the fragment is 108×119 mm; the width of the walls is 7.5−10.5 mm. Signs in the form of corners and line segments are scratched on the external surface (fig. 3: 3).

2. A necklace made of 14 glass beads.

– a round glass bead of light green color with seven “eyes” of white color. There is a blue circle with seven blue points inside of each “eye.” One point lies in the middle and six ones are situated around. The height of bead is 9.2 mm, the diameter is 9 mm, and the diameter of the opening is 2 mm. The diameter of the “eyes” is from 3.3 mm to 4 mm (fig. 3: 5a);

– glass beads of terracotta (3 ex.) (fig. 3: 5b,n,o) and white color (10 ex.) (fig. 3: 5c-m). Eleven beads are washer-shaped. The height of beads is from 1.3 mm to 1.7 mm; the diameter is from 2.8 mm to 3.5 mm. The diameter of the openings is from 0.9 m to 2 mm (fig. 3: 5b-m). Two more beads are two-section, in the form of a cylinder with a length of 4 mm and a diameter of 3 mm. The diameter of the openings is 1 mm (fig. 3: 5n, o).

The analysis of materials from the Scythian burials of barrows 5 and 6 from the “Garden” group near the Glinoe village shows that they belonged to ordinary commoners. Both graves were made in pits, which were the most common kind of funeral constructions of the Scythians in the northwestern Black Sea region from the late seventh to early third century BC.[7] It is most likely that the pits had a wooden cover, which was not preserved because of a robbery. The bronze arrowheads and the iron awl from the barrow 5 are quite common.[8]

The earring from the barrow 5 of the “Garden” group with a conical knob at one end attracts our attention. V. G. Petrenko has noted that such earrings appear in Scythian burials not earlier than the fourth century BC, but they appear only in Dniester region sites. On the other hand, he has pointed out that such items are quite well-known in sites dated from the sixth to fifth−fourth centuries BC in Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Bosnia, and connected their appearance with the Thracian influence in the northwestern Black Sea region.[9] For example, the discovery of three earrings of this kind in the Getian hoard at the Mateuţi village testify to it.[10] Earrings with conical knobs were found in the Scythian barrows 1 (near the Sukleia village) and 345 (near the Chobruchi village on the left bank of the Lower Dniester),[11] as well in burial 5 of the Nikolaevka I cemetery.[12] Such earrings with conical knobs on the endings were also found in burials 19/2 (pair), 57/1 (one earring from the western chamber), and 109/1 (pair) of the Glinoe Scythian cemetery of the third to second centuries BC.[13] At the present time, such items have also been found on the left bank of the Lower Danube in burials 23/1 (temporal ring) and 24/1 (earring) of the Mresnota Mogila cemetery.[14] The aforementioned complexes are dated from the last quarter of the fourth to the second centuries BC.

It should be noted that, along with the earring from burial 5/1, other finds from the barrows of the “Garden” group also indicate Thracian influence on Scythian material culture, and its chronology does not exceed the chronological scope of the last third or quarter of the fourth century BC. In particular, two clay cups (one has a typical protrusion in the upper part of the body; the other has a necked-in rim and accentuated rib) from the burial 2/2 of the “Garden” group and bronze torques, as well as two bronze fibulae from the burials 7/5 and 8/1 of the “Garden” group, are analogous to items in the complex 2/12 of the “Sluiceway” group.[15]

Ochre, a piece of which was found in burial 5/1 of “Garden” group, is an extremely rare find in the Scythian burials of the northwestern Black Sea region. Previously, “a piece of bright scarlet mineral” was discovered in the Danube-Dniester steppes in burial 1/1 of the Chervonyi Iar II group in the Lower Danube.[16] This complex dates from the turn of the fifth to fourth centuries BC judging by two segmented ribbed plaques of horse harness like a bird claw from the accompanying horse burial.[17] Traces of red ochre on facial bones of the skull were found in two more Scythian burials on the left bank of the Danube Region (burials 15/1 of the Gradeshka cemetery and 6/1 of the Kotlovina II cemetery). Both complexes date from the last quarter of the fourth through the first quarter of the third century BC.[18] Finally, traces of red ochre were fixed in nine burials in the Scythian cemetery of the third to second centuries BC near the Glinoe village: 53/1—the spots in the entrance to the catacomb on the ledge, in front of the entrance to the funeral chamber; 13/1, 31/1 and 69/2—on the stone slabs; 32/1—near the hand of the left arm; 116/1—near the right shoulder; 71/1—under pelvis of the deceased; and 89/3 and 111/2—the traces of coloring on the facial bones of the skull.[19]

One of the most interesting findings is that a piece of ochre from burial 5/1 was burned. We can argue with confidence that it, along with two shale pebbles, was part of the contents of an “incense cup.” Firstly, the same rite (a wooden cup with three burned pebbles inside) was identified in burial 8/3 near the Butory village on the left bank of the Lower Dniester, dated the third quarter of the fourth century BC.[20] In 2016 a wooden cup with three burned pebbles inside was discovered in burial 2/12 of the “Sluiceway” barrow group, which is dated to the turn of the third to last quarter of the fourth century BC.[21] The “Sluiceway” barrow group is located to the north and is in close proximity to the “Garden” barrow group. In 2017 the same two shale pebbles with the traces of fire were found during the excavations of burial 8/5 of the “Garden” barrow group, dated to the last quarter of the fourth century BC.[22] It has been previously observed that Scythians conducted a ritual of placing the cultic vessels with pebbles inside (“incense cup”) into burials in the Dniester region at least from the beginning of the third quarter of the fourth century BC.[23] Later, at the end of the fourth century BC, a handmade incense cup with pebbles inside received the widest distribution in burials in the Scythian cemetery of the third−second centuries BC near the Glinoe village.[24] This cemetery neighbors the “Garden” barrow group.

Based on the bronze trilobate arrowheads with slightly outstanding sleeves, burial 5/1 of the “Garden” group can be dated to the second half of the fourth century BC.

Barrow 6 of the “Garden” group, in spite of its external modesty, is interesting due to its construction elements and ritual elements. In particular, the bowl-like dimples, as in burial 6/1, until now have been known only in the floors of burial chambers in catacombs 2/3 (the last decade of the third century BC) of the barrow group “Chobruchi-Source” near Chobruchi village, Slobodzeia district,[25] and 25/1 (last quarter of the third−first half of the second century BC) of the Glinoe cemetery [26] on the left bank of the Lower Dniester. However, in 2015 a bowl-like dimple was found in the pit’s floor of burial 2/3 of the “Garden” group that dated to the last third of the fourth century BC.[27]

Further, one should note the pit’s division into two zones in burial 6/1 of the “Garden” group. The first one was designated for a woman with a child in her hands and the second one for another child who lay near the northern wall. The division of Scythian burial pits into two zones is rarely found in the Dniester region. On the right bank of the Lower Dniester, these are burials near the Purcary village: grave 1/5 (sacrificial food was separated by a block from the body of the deceased and the grave goods), which is dated to the last two decades of fifth century BC, and grave 1/6 (sacrificial food was in the rising of natural clay behind the head of the deceased), which is dated to the mid-fourth century BC.[28] On the left bank of the Lower Dniester the pit’s division into two zones was noticed in burial 2/2 near the Nikol’skoe village (sacrificial food and a part of the grave goods were separated from the body of the deceased and another part of the inventory with a block) dated to the turn of the fifth to fourth centuries BC.[29] The geographically nearest complexes where the pit’s division into two zones was noticed, however, were burials 2/12 and 3/2 of the “Sluiceway” group, which were studied in 2016. In burial 2/12, one zone was intended for an amphora, sacrificial food, and a knife and a wooden cup with pebbles inside, and the other zone for the body of the deceased and the rest of the grave goods.[30] In burial 3/2 of the “Sluiceway” group, the western part of the pit was used for sacrificial food, and the eastern part for the body of the deceased and the accompanying inventory.[31] These two complexes are noteworthy because the pit’s division was achieved due to the arrangement of “beds” from a layer of mixed clay and humus on which the bodies of the buried were placed.

A similar situation was found in burial 6/1 of the “Garden” group, where a second child’s bones lay on a “bed” made from a mixture of clay with humus at the northern wall of the pit. Apart from burials 2/12 and 3/2 of the “Sluiceway” group, as well as grave 6/1 of the “Garden” group near the Glinoe village, which were all made in pits, this rite was discovered in the funeral chambers of catacombs 48/2 near the Kochkovatoe village (second half of the fourth century BC) in the Danube region,[32] 95/1 and 100/1 of the Glinoe cemetery (third−second centuries BC) in the Dniester region,[33] 186/2 (first half of the fourth century BC) in the Mamai-Gora cemetery,[34] and 13/2 (second half of the fourth century BC) of the Bogdanovka enriching factory group[35] in the Lower Dnieper region. The appearance of this element is connected with Greek influence on the funeral rites of the Scythians.[36]

The placing of the amphora fragment under the child’s head on the “bed” in burial 6/1 of the “Garden” group is unusual. This element of the rite has been observed twice in the northwestern Black Sea region, and both times in the Scythian cemetery of the third−second centuries BC near the Glinoe village. Under the head of the deceased in the western chamber of catacomb 64/1 lay a fragment of a handmade vessel, and in the northern chamber of catacomb 65/1, a big fragment of amphora.[37] We argue that these ceramic fragments, like stones, were used to restore the border between the worlds of the living and the dead, which was broken by the death of a society member.[38] Destruction of this border could be due, inter alia, to the circumstances of the death.[39] Perhaps for similar reason (unknown disease?) after the burial a fire was made over the pit; its traces were fixed as a fireplace over the eastern part of the pit.

There was a highly interesting find of small beads in the woman’s necklace in burial 6/1 of the “Garden” group. This kind of adornment is very rare in the Scythian complexes of the northwestern Black Sea region in the fourth century BC. They are known only in seven burials: 11/3 near the Nagornoe village,[40] 5/1 of the Kugurlui cemetery,[41] 8/1 and 15/1 of the Mresnota Mogila cemetery on the left bank of the Lower Danube,[42] 3/1 of the Hadgider I cemetery in the Danube-Dniester interfluve,[43] 4/6 near the Nikol`skoe village on the left bank of the Lower Dniester,[44] as well as in grave 5/1 near the Nedelkovo village in the Dniester-Bug interfluve.[45] At the same time, small beads completely predominate in the necklaces and are found in other adornments that relate exclusively to women’s and children’s skeletons, unlike men’s skeletons, on the Glinoe Scythian cemetery of the third−second centuries BC.[46] The presence of the small beads in burial 6/1 of the “Garden” group (taking into account its widest distribution in the neighboring Glinoe Scythian cemetery of the third−second centuries BC and its absence in the other barrows of the “Garden” and “Sluiceway” groups) allows us to date this grave no earlier than the last quarter of the fourth—the turn of the fourth to third centuries BC.

Thus, the Scythian complexes in question demonstrate not only Thracian and Greek influence on the material culture of Scythians in the Lower Dniester in the second half of the fourth to early third century BC, but also its transformation at this time. This led to the appearance of such cultural phenomena as the late Scythian (third−second centuries BC) cemetery near the Glinoe village, the northern edge of which is 1.8 km southwest of the southern edge of the “Garden” group. This fact confirms the earlier point of view that Scythian steppe culture on the Lower Dniester did not cease at the end of the first third of the third century BC, but developed continually at least until the end of the second century BC.

References

Agul'nikov, S., E. Sava. 2004. Issledovaniia kurganov na levoberezh'e Dnestra [A Study of Barrows on the Left Bank of the Dniester]. Kishinev: CEP USM. (In Russian)

Andrukh, S. I., E. F. Sunichuk. 1987. “Zakhoroneniia zazhitochnykh skifov v Nizov'iah Dunaia [Burials of Wealthy Scythians in the Lower Danube]”. In Novye issledovaniia po arkheologii Severnogo Prichernomor'ia [New Investigations into the Archaeology of Northern Pontic Region], 38–46. Kiev: Naukova dumka. (In Russian)

Andrukh, S. I., G. N. Toshchev. 2009. Mogil'nik Mamai-Gora [Necropolis of Mamai-Gora]. Book IV. Zaporozh'e: Zaporozh'e National University. (In Russian)

Chetverikov, I. A., V. S. Sinika. 2009. “Skifskii kurgan kontsa III v. do n.e. u s. Chobruchi na levoberezh'e Nizhnego Dnestra [Scythian Barrow of the Late Third Century BC near the Chobruchi Village of the Left Bank of the Lower Dniester].” Starozhitnostі Stepovogo Prichornomor’ia i Krimu [Antiquities of the Steppe Zone in the Northern Pontic and Crimea] XV: 204–212. (In Russian)

Dzis-Raiko, G. A. 1965. “Raskopki mogil'nika v s. Nikolaevka na Dnestrovskom limane [Excavations of the cemetery in the Nikolaevka village on the Dniester Firth].” Kratkie soobshcheniia o polevykh issledovaniiakh Odesskogo gosudarstvennogo arkheologicheskogo muzeia za 1963 god [Concise Bulletins on the Fieldworks of the Odessa State Archaeological Museum in 1963], 59–68. Odessa: Maiak. (In Russian)

Gudkova, A. V. 1978. “Raskopki kurganov u s. Chervonyi Iar na Nizhnem Podunav'e [Excavations of the Barrows near Chervonyi Iar Village in the Lower Danube].” In Arkheologicheskie issledovaniia Severo-Zapadnogo Prichernomor'ia [Archaeological Research in the Northwestern Pontic Area], 182–193. Kiev: Naukova dumka. (In Russian)

Gudkova, A. V., E. F. Sunichuk. 1985. “Polevoi otchet Orlovskogo kurgannogo otriada Budzhakskoi arkheologicheskoi ekspeditsii v 1984 g. [Field Report of the Orlovka Barrow Team, Budzhak Archaeological Expedition, in 1984].” Nauchnyi arkhiv IA NANU [Scientific Archive of the Archaeology Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine]. No. 1984/3a. Kiev. (In Russian)

Gudkova, A. V., G. M. Toshchev, M. M. Fokeev, S. I. Andrukh. 1985. “Otchet o rabote Izmail'skoi novostroechnoi ekspeditsii v 1984 g. [Report on the Fieldworks of the Izmail Rescue Expedition in 1984].” Nauchnyi arkhiv IA NAN Ukrainy [Scientific Archive of the Archaeology Institute of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine]. No. 1984/158. Kiev. (In Russian)

Iarovoi, E. V. 1990. Kurgany eneolita – epokhi bronzy Nizhnego Podnestrov'ia [Barrows of the Eneolithic and Bronze Age in the Lower Dniester Region]. Kishinev: Shtiinca. (In Russian)

Meliukova, A. I. 1962. “Skifskie kurgany Tiraspol'shchiny (po materialam I. Ia. i L. P. Stempkovskikh) [Scythian Barrows of the Tiraspol’ Region (on the Materials of I. Ia. and L. P. Stempkovskis)].” Materialy i issledovaniia po arkheologii SSSR [Materials and Studies on the Archaeology of the USSR] 115: 114–166. (In Russian)

Nudel'man, A. A., E. A. Rikman. 1956. “Navershie i klad serebrianykh ukrashenii skifskogo vremeni iz Moldavii [Finial and Hoard of the Silver Adornments of the Scythian Time from Moldavia].” In Izvestija Moldavskogo filiala AN SSSR [Transactions of the Moldavian Branch of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR) 4 (31), 129–133. Kishinev: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel'stvo Moldavii. (In Russian)

Pankovskii, V. B., V. S. Sinika. 2017. “Rogovoi greben' iz skifskogo pogrebeniia u s. Glinoe [The Scythian Grave with a Horn Comb from the Lower Dniester Region].” Stratum plus 3: 343–359. (In Russian)

Petrenko, V. G. 1978. Ukrasheniia Skifii VII-III vv. do n. e. [Decorations of Scythia from the Fifth through Third Centuries BC]. Series: Svod Arkheologicheskikh istochnikov [Corpus of Archaeological Sources]. D4-5. Moscow: Nauka. (In Russian).

Polin, S. V. 2014. Skifskii Zolotobalkovskii kurgannyi mogil'nik V-IV vv. do n. e. na Khersonshchine [The Scythian Barrow Cemetery Zolotaia Balka, 5th–4th Centuries BC, Kherson Region]. Kiev: Oleg Filiuk Publ. (In Russian).

Razumov, S. M. 2011. Flint Artefacts of Northern Pontic Populations of the Early and Middle Bronze Age: 3200—1600 BC (Based on Burial Materials). Baltic-Pontic Studies. Vol. 16. Poznań: Adam Mickiewicz University.

Razumov, S. N., S. D. Lysenko, V. S. Sinika, N. P. Telnov. 2016. “Ritual'nyi kompleks rannego bronzovogo veka s levoberezh'ia Nizhnego Dnestra [The Early Bronze Age Ritual Complex from the Left Bank of the Lower Dniester].” Tyragetia. S.n. Vol. IX (XXV), no. 1: 175–194. (In Russian)

Redina, E. F. 1999. “Skifskii mogil'nik u s. Nedelkovo na severe Odesskoi oblasti [Scythian Cemetery near the Nedelkovo village in the North of Odessa Region].” Stratum plus 3: 75–80. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S. 2007a. Pogrebal'nye pamiatniki skifskoi kul'tury VII – nachala III v. do n.e. na territorii Dnestro-Prutsko-Dunaiskikh stepei [The Burial Sites of the Scythian Culture from the Seventh to Early Third Centuries BC in the Steppes between Dniester, Prut and Danube]. Abstract of the Candidate of Science (History) Diss., Moscow State University. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S. 2007b. Pogrebal'nye pamiatniki skifskoi kul'tury VII – nachala III v. do n.e. na territorii Dnestro-Prutsko-Dunaiskikh stepei [The Burial Sites of the Scythian Culture from the Seventh to Early Third Centuries BC in the Steppes between Dniester, Prut and Danube]. Candidate of Science (History) Diss., Moscow State University. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S. 2017. “Novye nakhodki predmetov zverinogo stilia na levoberezh'e Nizhnego Dnestra [New Finds of the Scythian Animal Style Items on the Left Bank of the Lower Dniester].” Povolzhskaia arheologiia [The Volga Region Archaeology] 3 (21): 306–317. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S., N. P. Telnov, O. A. Zakordonets. 2017. “Skifskii kurgan № 4 gruppy «Vodovod» na levoberezh'e Nizhnego Dnestra [Scythian Barrow No. 4 of the “Sluiceway” Group on the Left Bank of the Lower Dniester].” Samarskii nauchnyi vestnik [Samara Scientific Bulletin]. Vol. 6, no. 2 (19): 108–113. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S., N. P. Telnov. 2016a. “Skifskii kurgan № 1 gruppy «Vodovod» na levoberezh'e Nizhnego Dnestra [Scythian Barrow No. 1 of the Group “Sluiceway” on the Left Bank of the Lower Dniester].” Emіnak 4 [16]: 45–53. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S., N. P. Telnov. 2016b. “Skifskoe zakhoronenie s tamgoi rubezha IV-III vv. do n.e. s levoberezh'ia Nizhnego Dnestra [Scythian Burial with Tamga of the Turn of the Fourth to Third Centuries BC from the Left Bank of the Lower Dniester].” Novoe proshloe [The New Past] 4: 258–272. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S., N. P. Telnov. 2016c. “Skifskoe pogrebenie s litikom-skarabeoidom s levoberezh'ia Nizhnego Dnestra [Scythian Burial with Lithique from the left Bank of the Lower Dniester].” In Starodavne Prichornomor’ia [The Ancient Black Sea Region] XI, 488–499. Odesa: Odesa National University. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S., N. P. Telnov. 2017a. “Skifskie kurgany 2 i 3 gruppy «Sad» v Nizhnem Podnestrov'e [Scythian Barrows 2 and 3 from the «Garden» Group in the Lower Dniester].” Novoe proshloe [The New Past] 4: 286–306. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S., N. P. Telnov. 2017b. “Skifskoe pogrebenie s unikal'nym amuletom s levoberezh'ia Nizhnego Dnestra [Scythian Burial with a Unique Amulet from the Left Bank of the Lower Dniester].” Nauchnye vedomosti BelGU. Ser. Istoriia. Politologiia [Belgorod State University Scientific Bulletin. Series History and Political Science] 8 (257), issue 42: 5–12. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S., N. P. Telnov. 2017c. “Skifskoe pogrebenie s frakiiskoi fibuloi na Nizhnem Dnestre [The Scythian Grave with a Fibula of the Thracian Type from the Lower Dniester].” Stratum plus 3: 131–152. (In Russian)

Sinika, V. S., S. N. Razumov, N. P. Telnov. 2013. Kurgany u sela Butory [Barrows near the Butory Village]. Series: Arkheologicheskie pamiatniki Pridnestrov'ia [Archaeological Sites of the Dniester Basin]. I. Tiraspol': Poligrafist. (In Russian)

Subbotin, L. V., A. S. Ostroverkhov, S. B. Okhotnikov, E. F. Redina. 1992. Skifskie drevnosti Dnestro-Dunaiskogo mezhdurech'ia [Scythian Antiquities of the Dniester-Danube Interfluve]. Kiev: Preprint. (In Russian)

Telnov, N. P., I. A. Chetverikov, V. S. Sinika. 2016. Skifskii mogil'nik III-II vv. do n.e. u s. Glinoe [Scythian Cemetery of the Third–Second Centuries BC near the Glinoe Village]. Series: Arkheologicheskie pamiatniki Pridnestrov'ia [Archaeological Sites of the Dniester Basin]. III. Tiraspol': Stratum plus. (In Russian)

Terenozhkin, A. I., V. A. Il'inskaia, E. V. Chernenko, B. N. Mozolevskii. 1973. “Skifskie kurgany Nikopol'shchiny [Scythian Barrows in the Nikopol’ Region].” In Skifskie drevnosti [Scythian Antiquities], 113–186. Kiev: Naukova dumka. (In Russian)

Vanchugov, V. P., L. V. Subbotin, A. N. Dzigovskii. 1992. Kurgany primorskoi chasti Dnestro-Dunaiskogo mezhdurech'ia [Barrows of the Coastal Part of the Dniester-Danube Interfluve]. Kiev: Naukova dumka. (In Russian)

About the authors

Vitalij S. Sinika, Candidate of Science (History), is Leading Researcher in the Scientific Laboratory “Archaeology” at the T. G. Shevchenko Pridnestrovian State University and is Senior Researcher in the Scientific Laboratory of the Historiography and Field Methods in Archaeology at the Nizhnevartovsk State University.

Sergei D. Lysenko, Candidate of Science (History), is Senior Researcher in the Department of Chalcolithic and Bronze Age at the Institute of Archaeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

Nikolai P. Telnov, Candidate of Science (History), is Director of the Department of Ancient and Medieval Archeology in the Institute of Cultural Heritage of the Academy of Sciences of Moldova.

1. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016.↩

2. Pankovskii, Sinika 2017; Sinika, Telnov 2016а; 2016b; 2017b; 2017c; Sinika, Telnov, Zakordonets 2017.↩

3. Razumov, Lysenko, Sinika, Telnov 2016; Sinika, Telnov 2016c; 2017a.↩

4. Special thanks to S. N. Razumov, Candidate of Science in History, who executed the barrow’s plans and baulk profiles, burial’s plans, and their sections.↩

5. The ditch and two ritual pits are not described here. Their construction seems to be connected to the main burial of the Early Bronze Age (the Usatovo culture or Iamnaia (Pit Grave) culture). A similar archaeological situation was documented in barrow 4 of the “Garden” group (Razumov, Lysenko, Sinika, Telnov 2016) situated 70 m to the west-north-west of barrow 5.↩

6. Two of them are uninformative fragments of the walls, but the third one (1) is a fragment of the bottom.↩

7. Sinika 2007а, 12; Sinika 2007b, 55.↩

8. Sinika 2007а, 18−19.↩

9. Petrenko 1978, 34−35.↩

10. Nudel'man, Rikman 1956, 130−131, fig. 1: 1.↩

11. Meliukova 1962, 151, table 10: 2, 3.↩

12. Dzis-Raiko 1965, 66, fig. 4: 10.↩

13. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 975.↩

14. Gudkova,Toshchev, Fokeev, Andrukh 1985, 103-104, fig. 61: 6; 62: 3.↩

15. Sinika, Telnov 2017с, 135, fig. 2: 4.↩

16. Gudkova 1978, 188.↩

17. Gudkova 1978, 189, fig. 5:3, 4; Sinika 2017, 310.↩

18. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 924.↩

19. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 924. The barrow 116 was investigated by the authors in 2017; the materials are in print.↩

20. Sinika, Razumov, Telnov 2013, 59, 119, 125, 127, fig. 35: 1, 4; Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 840.↩

21. Sinika, Telnov 2017с, 134−135, fig. 4: 2−5.↩

22. Excavations were produced by the authors and the materials are being prepared for publication.↩

23. Sinika, Telnov 2017с, 145.↩

24. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 902−918.↩

25. Chetverikov, Sinika 2009, 211, fig. 2: 1, 5.↩

26. Sinika, Telnov 2017а, fig. 3: 2.↩

27. Sinika, Telnov 2017а, fig. 3: 2.↩

28. Iarovoi 1990, 47−48, 51, 53, fig. 20: 1, 21: 1.↩

29. Agul'nikov, Sava 2004, 21, fig. 11; Polin 2014, 368−369.↩

30. Sinika, Telnov 2017с, 144.↩

31. Sinika, Telnov 2016b: 261, 263−264.↩

32. Vanchugov, Subbotin, Dzigovskii 1992, 50.↩

33. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 767.↩

34. Andrukh, Toshchev 2009, 111, fig. 53.↩

35. Terenozhkin, Il'inskaia, Chernenko, Mozolevskii 1973, 163.↩

36. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 969; Sinika, Telnov 2017с, 144−145.↩

37. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 389, 393, 923−924.↩

38. Razumov 2011, 140.↩

39. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 922, 924.↩

40. Andrukh, Sunichuk 1987, 43, fig. 4: 11.↩

41. Gudkova, Sunichuk 1985, 31, table 68: 9, 10.↩

42. Gudkova, Toshchev, Fokeev, Andrukh 1985, 83, 91, fig. 50: 11; 55: 6.↩

43. Subbotin, Ostroverkhov, Okhotnikov, Redina 1992, 23, fig. 20: 17.↩

44. Agul'nikov, Sava 2004, 44.↩

45. Redina 1999, 77.↩

46. Telnov, Chetverikov, Sinika 2016, 850, 853, 858, 868, 874, 876−877, 884.↩

Figures

Fig. 1. Plans (1) and profiles (2) of barrows 5 and 6 of the “Garden” group on the left bank of the Lower Dniester.

Fig. 2. Scythian burial of barrow 5 (1, 2) of the “Garden” group and its inventory (3-10).

Fig. 3. Scythian burial of barrow 6 (1, 2, 4) of the “Garden” group and its inventory (3, 5).