Original article

DOI 10.18413/2312-3044-2019-6-1-17-41

Liminality in the Ethnohistory, Culture, and Kinship of the Nagaibaks*

S. Iu. Belorussova

1) Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology

and Ethnography (Kunstkamera),

Russian Academy of Sciences

Universitetskaia emb. 3, St. Petersburg, 199034, Russia

E-mail:

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

2) National Research University “Higher School of Economics”

Soiuza Pechatnikov st. 16, St. Petersburg, 190121, Russia

E-mail:

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

Abstract. . The Nagaibaks as an ethnic group originated in 1736 after the establishment of the Nagaibak fortress, which brought together natives of different backgrounds from adjacent areas and awarded them the status of Cossacks (on condition of their baptism). Later, after their resettlement to the New Line in 1842–43, the Nagaibaks formed a peculiar community: their membership in a military estate and the inclusion of peoples of different traditions and creeds helped them to become “a border people” in spatial and sociocultural dimensions. In turn, this “liminality” allowed the Nagaibaks to unite opposing traits within their ethnicity, such as hospitality and rivalry, and openness to innovation (in terms of active participation in ethnic projects) and closeness to traditions (in terms of preserving rituals of kinship). At various points in their history, the Nagaibaks turned to either openness or closeness, or a combination of both. In the Soviet period, an emphasis on closeness allowed them to preserve their culture (“introvert mode”). In the post-Soviet period, on the contrary, the Nagaibaks mobilized their ethnicity through openness (“extrovert mode”). This dynamic feature of Nagaibak ethnicity made it possible to transform themselves from the spatial mobility of the past to the activization of ethnicity in the present. Through their development at the crossroads of different types of cultures (nomadic and sedentary, Christian and Muslim, European and Asian) the Nagaibak ethnic group became open-minded and adaptable, while its nomadic and Cossack sociocultural heritage led to mobility and flexibility in attitudes.

Keywords: Nagaibaks, ethnicity, borderland, mobility, sedentism, tradition, novation

Copyright: © 2019 Belorussova, S. Iu. This is an open-access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source, the Tractus Aevorum journal, are credited.

УДК 394

Состояние пограничья в нагайбакской этноистории, культуре и родстве

С. Ю. Белоруссова

1) Музей антропологии и этнографии

им. Петра Великого РАН (Кунсткамера)

199034, г. Санкт-Петербург, Университетская наб., д. 3

E-mail:

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

2) НИУ «Высшая школа экономики»

190121, г. Санкт-Петербург, ул. Союза Печатников, д.16

E-mail:

This e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it

Аннотация. Этничность нагайбаков зародилась в 1736 г. после образования Нагайбакской крепости, в которую собирали окрестных инородцев разного происхождения и после (при условии) крещения наделяли казачьим статусом. Позднее, после их переселения на Новую линию в 1842–1843 гг., нагайбаки обособились в особую группу: принадлежность к военному сословию, соседство с народами разных традиций и верований помогли нагайбакам стать «людьми границы» в пространственном и социокультурном значении. «Пограничное состояние» позволило им объединить оппозиции в своей этничности — гостеприимство и соперничество, открытость новациям (в виде активного участия в этнопроектах) и закрытость традиций (в проявлении ритуалов родства). В разные периоды истории нагайбаки «включали» то открытость, то закрытость, то их различные сочетания. Акцент на закрытости дал возможность сохранения своей культуры в советское время («интровертность»). В постсоветский период, напротив, они мобилизовали свою этничность через открытость («экстравертность»). Динамизм в этничности обусловил переход нагайбаков от пространственной мобильности в прошлом к этнической активизации в современности. Находясь на перекрестке разных типов культур — кочевой и оседлой, христианской и мусульманской, европейской и азиатской — нагайбакская культура стала восприимчивой и адаптивной, а кочевое и пограничное казачье социокультурное наследие послужило основанием мобильности и маневренности в действиях нагайбаков.

Ключевые слова: нагайбаки, этничность, пограничье, мобильность, оседлость, традиция, новация

Ethnic dynamics are associated with exploration, the crossing of borders, and the transformation of borderlands into transboundary areas. According to F. Ratzel, “there is not a single nation today that lives in the territory where it originated and will always remain there” (1882, 49). F. Bart has shown that in multiethnic communities, borders are often permeable and form a domain of new relationships. Moreover, “the safety of an ethnic group depends on the stability of its border,” which is formed through “situations of social contacts between people of different cultures” (Barth 1969, 20–24). For his part, E. Leed has posited that “boundaries are created by those who cross them” (1991, 17), and borderlands peoples have distinctive cultures and worldviews. As the border has always been marked by mobility, Leed compared it with the concept of a “path” and defined the borderlands as a “world with its own logic, order, freedoms and restrictions, and not just the border between the inner and outer spaces” (Leed 1991, 79). Meanwhile, the border has always been associated with group mobility, given the vastness of networks and contacts (Golovnev 2018; Urry 2012; Ingold 2011).

Cross-border regions have played a key role in Russian history, since “Russia is a border state, a European periphery and an outskirt from the Asian side” (Solov’ev 1988, 709). The Russian practice of developing borderlands (or “outskirts”) differed significantly from the Western experience of frontier colonization. Long-term contacts and interactions between cultures and traditions took place on the outskirts. Describing their specifics, A. Golovnev notes, “In Eurasia and Russia, this border space was not a place for meeting and confrontation between different civilizations, but an arena for renewing old ties and redistributing power between aging and newly emerging metropolises” (2015, 532–533).

The Cossaks, a driving force of the Russian borderlands, were naturally associated with borderlands, campaigns, robberies, the atamans’ authority: “The Cossack community only looked solid from the outside, and from the inside it was a cauldron of different customs, interests, and ideas” (Golovnev 2015, 335). Cossacks came from various ethnicities. Thus, for example, the Terek and Greben Cossacks, which appeared in the late sixteenth century, included Kabardins, Chechens, Kumyks, Nogais, Georgians, Armenians, and Circassians.

Being on the borderland, the Cossacks, in their external affairs, were guided by conflicts, delving into the contradictions and intrigues of the neighboring powers, taking sometimes one side, sometimes another, sometimes several sides in a row. This turbulence led to a peculiar borderland mentality in which maneuver prevailed over constancy (Golovnev 2015, 335).

Cossacks created a powerful colonizing impulse in the borderlands:

Even being outcasts and rebels, they were in their own way a product of the state and kept in touch with it. The paradox was that the more outcasts the state pushed out, the wider the borderlands that they mastered became. Crossing borders, “the unwanted people” opened the way for the state that followed them (Ibid., 335).

Under such conditions of Russian colonization, new communities formed at the intersection of traditions and cultures. These communities subsequently created separate nations with their own territories, traditions, realia, and myths. In the turmoil of the southern Urals outskirts, at the crossroads of borders and trade routes, less than 300 years ago, the history of Nagaibaks began.

The emergence of the community and gaining ethnic traits

The emergence of the Nagaibaks originates with the colonial policy of the Russian Empire in the 1730s–40s. During this period, the Russian state began construction of the Orenburg defensive line in the steppe belt of the Urals. At the same time in 1735–41, the state also suppressed the Bashkir rebellion. Under a policy of “cautious colonization,” the newly formed borders were strengthened by creating a “living border” layer made up of the Cossacks.

According to the head of the Orenburg expedition, chief secretary of the Senate I. K. Kirilov, no fortresses or population groups existed that could offer military support in the southern Urals in the 1730s. As a result, the authorities decided to attract baptized iasak newcomers who did not support the Bashkir uprisings and who were interested in getting rid of perceived rivals. On February 11, 1736, Empress Anna Ioannovna decreed that “the Ufa newly baptized, for their faithful service, be assigned to the Cossack service... and the iasak be removed from them.”[1]

The Nagaibak fortress was founded in 1736 at the site of the Bashkir revolts led by Kusium and his son Akai. The various neighboring indigenous populations were collected in it, and after (and on condition of) baptism they were given Cossack status. At the very beginning of the fortress’s construction, 261 converts received Cossack status.[2] In 1737, a staff was established consisting of an ataman, 6 centurions, 6 clerks, and 586 Cossacks.[3] By the end of the construction of the Nagaibak fortress, the number of Cossacks increased to 1,250.[4] By the 1760s there were 1,359[5] (approximately the same number as in 1795).[6]

In the 1740s, a branch of the Kazan Conversion Office was established in the Nagaibak fortress to freely carry out mass baptisms among natives. The “Mohammedans” (Tatars, Bashkirs, Teptiars, and Kyrgyz) and the “idolaters” (Cheremis, Mordovians, and Chuvashs) were converted in the fortress. Some of the converts became Cossacks; others remained iasak peasants.

The Nagaibak fortress gradually became a gathering place for the converts, and exerted control over the performance of Christian rites and official orders. At later points in history, the fortress received not only natives, but also “Asians” who escaped from captivity. A decree from the State Collegium of Foreign Affairs on February 16, 1752, stated that non-Russian citizens who fled Kyrgyz-Kaisak captivity should be returned, except for those who “wish to receive holy baptism” (Rychkov 1762, part 1, 192). By 1760 there were sixty-eight fugitives who received baptism, including Persians, Arabs, Bukhara and Karakalpaks (Ibid.). N. P. Rychkov, who traveled through Ufa province in 1769, referred to the inhabitants of the fortress as “a collection of various Asian peoples” (1770, 68).

The emergence of self-awareness

After the Pugachev uprising, the Nagaibak and Bakalinsk settlements lost their military-strategic, religious, and administrative significance. The Conversion Office closed and the number of native baptisms significantly decreased. Continued colonization by the Russian Empire in the early nineteenth century necessitated the construction of new Cossack-fortified settlements on the Uisk line, running from Orsk to the settlement of Berezovskaia (Atnagulov 2015, 73). Kazakh nomads were located there, and the formal occasion for establishing the New Line was the ongoing clashes between the nomadic Bashkir and Kazakh clans. The policy separated the warring peoples with a strip of 120-150 miles, which was to be settled by Cossacks.

Among the new immigrants were servicemen from fortresses and villages in Orenburg province, including Nagaibak and Bakalinsk, and adjacent villages. In 1842, the Cossacks of Nagaibak (250 people) and Bakalinsk (1,531 people) and their families began to resettle in three districts of Orenburg province.[7]

Cossacks were not enthusiastic about the resettlement, as it meant a loss of contact with their homeland and relatives who remained there. To date, there is scant documentary evidence of the Nagaibaks moving to the New Line. However, the emotions of moving, feelings of loss and doom, and unwillingness to leave their lands, are well preserved in the people’s memory. According to the testimony of E. A. Bekteeva, “the Nagaibaks, especially women, longed for their old, naturally rich homeland: when they came with buckets for water, the Nagaibak women sat on the riverbank and wept bitterly” (1902, 179). The hostility to leaving one’s land was connected, among other things, to servitude.

The shared emotions and difficulties in settling in a foreign land further rallied the immigrants, who received a special name at the place of their former deployment: (Nagaibak fortress) Nagaibaks. The resettlement, though, divided them into three groups: southern (Orenburg), northern (Chebarkul), and central (actual Nagaibak). New settlements (villages) were built on the new site, and they received land allotments as a salary for their Cossack service, gradually turning from border guards into settled farmers.

Ethnographers and eyewitnesses positively evaluated the contacts made by the Nagaibaks with neighboring peoples, including with nomadic Kirghiz-Kaisaks: “The Kirghiz roamed around the Cossacks, and it was considered special evidence of courage for them to steal someone else’s herd. However, there is no particular enmity between the Nagaibaks and the Kirghiz” (Bekteeva 1902, 179). A priest of the Fershampenuaz parish M. Sofronov noted:

The Nagaibaks had a more or less close acquaintance with the Kirghiz, since they let Kirghiz herd their livestock and, thus, had frequent relations with them: they went to see their cattle, shear their sheep or just to visit. Kirghiz regaled them with kumis, sometimes horsemeat; of course, the Kyrgyz themselves often visited the Nagaibaks (Sofronov 1898, 837).

Thanks to their Cossack mobility, Nagaibak men actively communicated with the Russians and fluently spoke their language (Nebolsin 1852, 22). Bekteeva notes the good relationship between Russians and Nagaibaks: “Cossacks treat Russians with respect, but not considering themselves inferior” (1902, 180), and the peoples “live in harmony” (1902, 166). Sofronov, on the other hand, describes them as a separate group: “The Nagaibaks had few relations with the Russians, and therefore could not become Russified” (1898, 837). According to him, Nagaibaks were a closed community based on alienation from other peoples, who, in turn, perceived the Nagaibak Cossacks as “strangers.” Being surrounded by two different cultures, Russian and Kazakh, Nagaibaks retained their particularity, expressed in isolation, including marital endogamy and reliance on kinship-neighborly relations.

Between the 1870s and 1910s the Nagaibak ethnicity was shaped in part by a religious rivalry between Orthodox and Muslim missionaries. Both groups convinced the Nagaibaks of their particularities. Orthodox preachers highlighted the difference between Nagaibaks and Muslim Tatars, to whom they were related by language. Muslims focused on the difference between Nagaibaks and Russian Cossacks, to whom they were related by religion. Orthodox missionaries had difficulty working with the Nagaibaks, since previously they had experience working with inorodtsy who were iasak peasants, not active Cossacks. One should note that they worked with the central Nagaibaks under special conditions personally set by Kazan orientalist N. I. Il`minskii, known for his special approach to attracting natives to the Orthodox faith.

According to contemporaries, under the influence of the missionaries, “the Nagaibaks (of the central group—S. B.) go to church in crowds, and the boredom on their faces gives way to a tear of tenderness during service” (Bekteeva 1902, 178). The priests, in turn, not only introduced the Nagaibaks to the faith, but also emphasized the uniqueness of Nagaibak culture and its independence from Tatar culture. The southern Nagaibaks were influenced by both Orthodox and Muslim missionaries. The Orthodox clergy framed conversion to Islam as the breakaway of Nagaibaks from Christianity. In fact, some of the Nagaibak ancestors professed the Muslim faith before their baptism, so for them the conversion to Islam was a return to their previous religion. The Orthodox missionaries failed to “save” the southern Nagaibaks from Mohammedan influence: all the villages of the southern group converted to Islam.

External factors affected the three groups in different ways. The southern Nagaibaks not only changed their religion, but also their ethnic identity; today the descendants of the Orenburg and Orsk Nagaibaks consider themselves Muslim Tatars. The central and northern groups remained committed to Orthodoxy (with the exception of individual villages, for example, Trebia). By the early twentieth century, it was the central Nagaibaks that formed a group with their own traditions, rituals, religion, folklore, legends of origin, and stories about Cossack feats of arms (Belorussova 2016, 50).

Picture 1

The Nagaibaks of Parizh. The early twentieth century.

The Archive of the Museum of Parizh Village

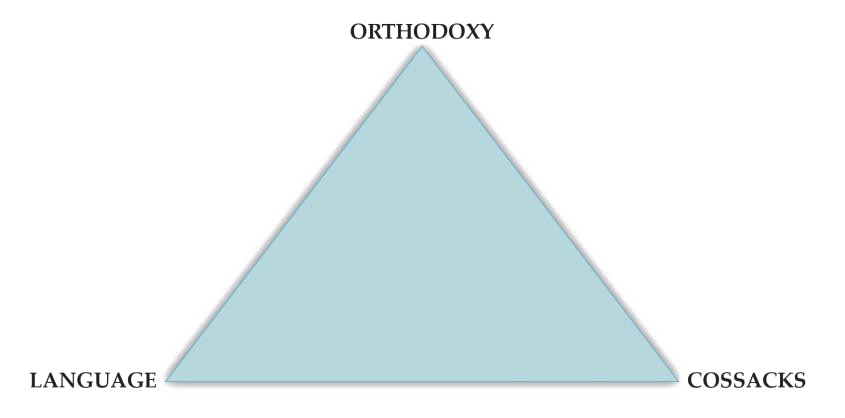

By the early twentieth century the Nagaibaks formed the boundaries of their ethnicity as a triad of markers: Orthodoxy, language, and Cossack status. It was this triad that prevented their merging with other ethnic groups. First, by faith, they could not get closer to the Muslim peoples. Second, their Turkic language was an obstacle to the merging of the Nagaibaks with the neighboring Russian Cossack population. Third, the social status of the serving Cossacks separated them from the Kriashen peasants.

Graph 1

The triangle of ethnic identity of the Nabaibaks

The Nagaibaks did not side with any of the parties in the revolutionary events of 1917 and, according to contemporaries, the news of the revolution came to them much later. Dramatic events took place during the Civil War. Individual Nagaibaks of Ostrolenskii and Kassel`skii have recalled their support for the Whites. Many Cossacks died in the hostilities, and some of them followed Dutov to China. The Nagaibaks of Parizh fought on both sides, but eventually supported the Reds. Today, the village of Parizh promotes its connection to V. K. Blucher’s headquarters, which was once located there during the Civil War.

Repression and denial

The 1930s saw the beginning of a shift in Nagaibak ethnicity. Following the 1939 census, the Nagaibaks were no longer considered a separate people and were instead ranked among the Tatars. Soviet repressions were directed against all the foundations of Nagaibak ethnicity: Orthodoxy (atheist propaganda), Cossack status (politics of Decossackization) and Nagaibak dialect (replaced by the Tatar language in the schools and in official communication).

At the same time, the Nagaibak nationality was excluded from the register of peoples in censuses and documents (birth certificates and passports) so that the people formally ceased to exist. In addition, instead of the prevailing positive image of the brave Nagaibak Cossacks in the past, a derogatory version of their forced baptism was launched into circulation (“they were forcibly baptized in a filthy swamp”). Since that time, public education has been conducted in the Tatar language with the involvement of Tatar teachers, although in terms of self-awareness and the perception of their neighbors (Russians and Kazakhs), Nagaibaks were still considered an independent community. In the Soviet era, being a Nagaibak was uncomfortable, unstable, and even formally impossible.

Non-recognition of the Nagaibaks as a separate people led them to reject the designation of themselves and their culture as “Tatar.” Central Nagaibaks worried about the imposed Tatar ethnicity: “I am not a Tatar, I feel it here [gesture pointing to the heart].” [8] At the same time, they had no hostility to the Tatars; on the contrary, many were connected with them by friendly relations and family ties. In many ways, the naming of the Nagaibaks as Tatars produced a “contrary effect,” a surge in the national movement since the mid-1980s.

Under such conditions, the Nagaibaks were inclined to accept the concept of the “Soviet man.” When communicating with different people, they ascribed their territorial affiliation to their respective district, region, and country, rather than to their ethnicity. The Great Patriotic War, collectivization, the development of the virgin lands played a large role in the ethnohistory of the “Soviet” Nagaibaks. In residents’ contemporary memories, the Soviet Nagaibak was a collective farmer and an active participant in amateur organizations.

Cossack (combat) identity was expressed with special reverence for Nagaibak participation in the Great Patriotic and Afghan wars. At the same time, the Nagaibaks retained distinctive funereal customs, including the rite of Ash Bireu, Parental Days, and Trinity.[9] Nevertheless, during the lives of two generations (1940s–1980s), the Nagaibak ethnicity remained latent, characterized by closeness and introversion (Golovnev 2013, 8).

Revival and revitalization

The ethnic revival of the Nagaibaks coincided with the period of post-Soviet crisis. The vectors of religious, Cossack, and ethnocultural revitalization converged in this development. In addition, Nagaibak leader Aleksei Mamet’ev, who turned out to have the ideal qualities needed at that moment for decisive ethnic self-determination of the Nagaibaks, played an important part in ethnic mobilization. Having worked most of his life far from the Nagaibak homeland, Mamet’ev could look at it from an outsider’s perspective. At the age of almost sixty, he began work on the first museum in Fershampenuaz. The museum opened on May 6, 1985, a date that marked the rebirth of the Nagaibak ethnicity.

Picture 2

A. M. Mamet`ev. The family archive of the Mamet`evs

Mamet’ev’s activities were an impetus for the activation of Nagaibak cultural life. Local residents founded folk groups in every Nagaibak village—Fershampenuaz (Sak Sok), Parizh (Chishmelek), Ostrolenskii (Sarashly), and Kassel`skii (Gumyr). Subsequently, museums opened in the same villages with a focus on Nagaibak material culture. Museums became not just centers of folk culture, but a sacred space for preserving the Nagaibak heritage. The Ostrolenskii museum hosted traditional holidays and included a prayer room for Orthodox rites, including baptism.

A. M. Mamet’ev’s most important project was the acquisition by the Nagaibaks of the status of a separate people. He corresponded with Chairman of the Council of Nationalities of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR R. N. Nishanov and Director of the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the USSR Academy of Sciences V. A. Tishkov. In June 1993, the Supreme Council of the Russian Federation adopted the “Fundamentals of the Legislation of the Russian Federation on the Legal Status of Indigenous Minorities,” which included the Nagaibaks in its list of indigenous peoples. In response, Nagaibaks began to change their passports so that “Nagaibak” appeared in the column for “nationality.” This period can be considered one of “Nagaibak euphoria,” as a new sense of ethnic importance appeared in people's self-consciousness.

Today, the ethnicity of the Nagaibaks is supported by the implementation of ethnological projects: the creation and operation of museums, folklore groups, festivals, conferences, and language electives. Over the past few years, Nagaibaks have participated in religious projects, such as the restoration and construction of Orthodox churches in their villages. According to a recent survey, their ethnic identity makes most Nagaibaks feel proud.

Picture 3

A contemporary Cossack. Photo by S. Iu. Belorussova. Village of Parizh

Picture 4

A Kassel`skii Nagaibak girl. Photo by S. Iu. Belorussova. Kassel`ski

According to the 2002 census, there were 9,600 Nagaibaks, of whom 7,394 lived in the Nagaibak district of the Chelyabinsk region. The 2010 census recorded 8,148 Nagaibaks, most of whom (6,127 people) were representatives of the central group (Atnagulov 2015, 187–196). At the same time, according to private surveys and observations, many Nagaibaks (especially representatives of the northern group) are recorded in the census as “Russians;” however, they recognize themselves as Nagaibaks.

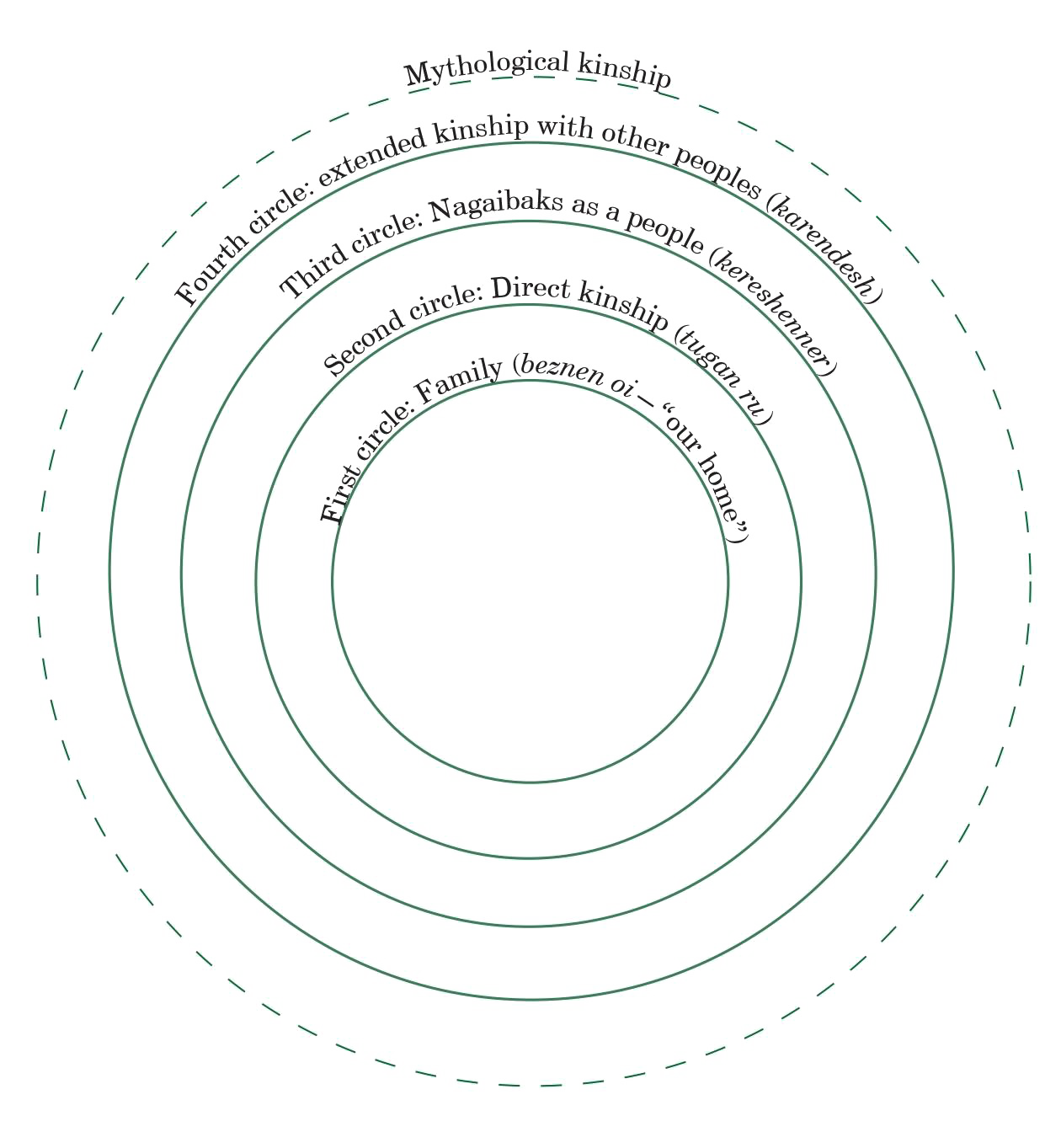

Boundaries of kinship

In the Nagaibak language the word for “relations” and “kin” is tugan; its derivative tugannyk is translated as “kinship,” while tugannar means “relatives.” Relatives of several generations are referred to as tugan, and the boundaries of kinship are established within the families themselves and their own kin. In one situation, tugan can be used only in relation to consanguinity, in another it can refer to all Nagaibaks and even neighboring peoples. In this regard, clearer boundaries are determined by the tugan ru, or “kinship.” The boundaries of kinship among the Nagaibaks can vary depending on the situation or mood. To demonstrate kinship technologies among Nagaibaks, it is convenient to define “kinship circles,” from the narrowest (family) to the broadest (connection with ethnically close peoples) (Belorussova 2017, 88–95).

Graph 2

“The circles of kinship” of the Nagaibaks

First circle: Family (beznen oi—“our home”)

The family is the most stable unit of kinship. To date, the Nagaibak language does not have a special word for “family.” Usually it is referred to as beznen jort or beznen oi, “our home.” The family includes close relatives: the parents of the husband and wife, and their brothers and sisters and their children.

Family is the most united and closed “circle.” Nagaibaks show the strength of family contacts in contrast to the relationship of indirect kinship and relations by marriage: jide bajaini ber bure ashagan, е ike agayny jide buren еingenner (“one wolf ate seven brothers-in-law, and two brothers defeated seven wolves”). At the same time, violation of cohesion (for example, loss of contact between brothers and sisters, parents and children) and closeness [in Nagaibak they say auyzyn tulyk kara kan busla da, keshe kilgech tokerme—“even if the mouth is full of blood do not spit it out in front of the others”] is reprehensible within the community. At the same time, strong family kinship is inherent in its organic narrowness, and is noticeably inferior to the next “circle” of tugan ru—the kinship among several tribes and generations.

Second circle: Direct kinship (tugan ru)

An old Nagaibak proverb states: Sigez tenke akchan bulganchy, sigez byuyn tamyryn bulsyn. This translates as “do not have eight rubles, but have a relative in the eighth lineage.” Many agree that wealth is measured not by money, but by the number of relatives. By tradition, a Nagaibak needs to maintain contact with a circle of seventh to eighth degree of relatives, although today such a “prescription” is difficult to achieve. Due to the endogamy of the Nagaibak community, the seventh-eighth degree of relatives includes residents of not only one’s village, but also neighboring ones. Since the definition of “one’s own” requires the presence of “someone else’s,” the Nagaibaks have significantly “narrowed” the boundaries of kinship. Today, many Nagaibaks recognize “blood” relatives to the second and third degree. For example, Nagaibak woman Nadezhda Firsova considers her second cousins to be “blood” relatives, but does not refer to her third cousins as relatives;[10] Egor Isupov even reasoned that among the Nagaibaks “second cousins are not considered close relatives.” [11]

Kinship rituals of Nagaibaks are rather restricted in terms of who may participate. It is accepted that all relatives have the opportunity to bury the dead, “sit the night” before the funeral, and participate in the burial. However, at the commemoration ceremonies the circle narrows, as only relatives no further than two lineages apart are usually invited to the commemoration. At the same time, close relatives have more obligations. According to Evdokiia Isaeva, cousins “must dig the grave for the deceased,” while second cousins do not have such obligations.

Nagaibak villages have different “clans” under the same names. In the Ostrolenskii there are four clans of the Iuskins, in Nezhinka there are two clans of the Uriashevs, and in other Nagaibak villages there are several clans of the Batraevs, Kinzins, Iakovlevs, Fedorovs, and others. Each kin knows the approximate framework of “their own” and “the other” lineages among their namesakes. For example, all Iuskins are related by kinship, but the isolation of each of the four kins has already become a tradition. According to observations, representatives of dynasties can communicate and help one another, but it is not customary to violate the boundaries of kinship. There is an unspoken prohibition for a representative of a different clan to participate in an “alien” event.

Third circle: Nagaibaks as a people (kerеshenner)

The kinship between the Nagaibaks, both within a specific group and the entire nation, is included in this “circle.” Since the Nagaibaks were mainly relatives to each other within the same village, it was considered common to find a marriage partner in the neighboring Nagaibak village. According to Emma Georgievna from the village of Popovo, “When I was little, no one married Russians here; we went to Bolotovo and married Nagaibak women there.” [12]

The Nagaibaks from different villages of the same group are connected by a “web” of kinship: for example, when meeting one another, the Nagaibaks begin by looking for related lineages. This way they manage to make friends more firmly, and sometimes even become related. Nikolai Vasiliev from Ostrolenskii thus found his third cousin from Kassel`skii:

Once we went to Kassel`skii and came in for tea, and there was an elderly woman whom I did not know. She asked: “Son, where are you from?”— “We are the Vasilievs.”—“Oh, Kodai [God—S. B.], you are my relative.” It turned out that we were third cousins. After that we kept in touch until she died. [13]

The northern and central groups of Nagaibaks bind themselves by one fate and define one another as neighboring relatives. They believe that the relocation of 1842–43 divided a once united people, and in some cases even split families: “After the resettlement, they came to visit each other and identified relatives by ornaments on the window frames of the house,” noted Natalia Iuskina. The Nagaibaks of both groups refer to each other in different ways: the Chebarkul Nagaibaks call the residents of the Nagaibak district the gumbeyler (“Gumbeis”), from the river of Gumbeiskaia, along which the villages of the central group are located. Those residents, in turn, define the inhabitants of the northern group as warlamlar (“Varlamovites”) from one of the villages inhabited by the Chebarkul Nagaibaks.

Fourth circle: extended kinship with other peoples (karendesh)

Geographically and mentally, the Nagaibaks are at the crossroads of cultures: Turkic and Russian, Orthodox and Muslim. In Soviet times, the Nagaibaks sought to be closer to the Russians, and sometimes called themselves “Russians.” Even today some define themselves as “Russian” and some speak of a double identity of “Nagaibak-Russian.” The proximity to the neighboring Kazakh population is manifested through the language: some Nagaibaks speak Kazakh, and some Kazakhs speak the Nagaibak language. The former head of the Nagaibak district, Kazakh Kairbek Seilov, was proud that he could communicate with the Nagaibaks in their native language: “When people come to see me, I fluently speak with them in Nagaibak.”[14] It is possible that this skill predetermined the success of Seilov in his leadership, as it helped a Kazakh become “one of us” for the Nagaibaks.

The closest community to Nagaibak is considered to be Kriashen. The two peoples have a similar culture, history, and traditions; their modern ethnocultural projects have a lot in common. Some local residents, as well as scientists, politicians, and public figures, consider the Kriashen and Nagaibaks to be “one people.” When meeting one another, the Nagaibaks and the Kriashen try to speak the same language and discuss the similarity of their traditions and rites. From time to time, in conversations, the Kriashen and the Nagaibaks call each other tugan, exchange hugs, and invite one another to visit. At the same time, “kinship” with the Kriashen is situational by nature. Cultural figures are more involved in these connections, and the “strengthening” of kinship depends on the intensity of mutual contacts.

According to some Nagaibaks, they are related by kinship with the Nogais, Arabs, Turks, Gagauz, and others. Nikolai Vasiliev said that the Nogais once called him tugannar because in the places of modern residence of the Nagaibaks “the Nogai Horde had pastures.” A resident of Ostrolenskii found similar “dances of the Gagauz and the Nagaibak.” Nagaibaks spoke about the feeling of linguistic kinship with the Tatars and Bashkirs when in a different (most often Russian-speaking) environment, or about their closeness in religion to Russians (for example, if they are surrounded by Muslims). The kinship of the Nagaibaks with other peoples is often “discovered” during a search for their own ethnic origins. This relationship is conditional and depends on the specific situation and context.

Mythological kinship can be extended beyond the general “kinship circles.” Nagaibaks might include into their community famous historical figures and contemporaries. According to Piotr Mineev, “the history of the Nagaibaks comes from Derzhavin and Boris Godunov; they are Kriashens.” In addition, the Nagaibaks include the “commander of the Brest Fortress Gavrilov, and Mendeleev.” Parizh resident Iuri Batraev believes that “Tiutchev and Derzhavin came from the Kriashen, and Suvorov's father was the governor of the Nagaibak fortress for eight years.”

In 2012, the Nagaibaks traveled to European cities, from which the names of their villages came. Nagaibaks believe that their ancestors participated in the Napoleonic Wars and the foreign campaigns of the Russian army of 1813–14. Thus, they took the trip as a tribute to their families and planned to “find their abandoned relatives.” On this occasion, project participant Nadezhda Firsova commented: “If our grandfathers were there, then didn’t they leave offspring? I will see our people on the spot.”[15] Thus, a familiarization with legendary figures of history and modernity, as well as with “alien” communities, is an example of kinship as an ethnic technology of Nagaibaks.

Duality of Frontier

The state of borderland, which is applicable to the ethnic history, culture, and kinship of the Nagaibaks, developed a duality that in turn formed the basis of Nagaibak identity and culture.

Mobility-sedentarity. Today, Nagaibaks represent a classic sedentary community with the values of “homeland” and “home comfort.” According to a distributed questionnaire, the Nagaibaks consider “industriousness,” “hospitality,” and “cleanliness” to be their main positive ethnic features. By hard work, they mean “the ability to build a house” and “to monitor the household.” For them, hospitality is the ability to competently meet, treat, and entertain guests in one’s home; cleanliness is “the ability to keep one’s house in order.” There are many rituals and customs regarding these positive characteristics of the Nagaibaks (“help” in building a house, songs and ditties at the meeting of guests, and so forth.) To demonstrate the difference in the cultures of neighboring peoples—Kazakhs (nomads) and Nagaibaks (settled)—there is a saying: “If the Nagaibak gets rich, he will build a house. If the Kazakh gets rich, he will buy a horse.”

However, many Nagaibaks believe that they originally belonged to a more mobile community, as some settlers of the Nagaibak fortress came from the steppe nomads. According to N. Vasiliev, a resident of Ostrolenskii, the older residents called themselves “steppe dwellers,” and old songs recall how the Nagaibaks “set up white yurts.”[16] Some illustrate their “nomadic spirit” with a love of horses. Among the Nagaibaks there are many who are involved in horse breeding and horse racing. The Nagaibaks are proud of the mobility of their ancestors and their readiness for action: “When there is no war, plow, sow, give birth to children, and go about your business quietly. But when you hear a trumpet, mount your horse, saber in hand, and march.”[17] It is possible that Nagaibaks, due to their borderline state, were able to combine the qualities of locality and magistrality as characteristic features of their ethnicity (Golovnev 2012, 11–12).

Openness-closedness. The ethnicity of the Nagaibaks has developed from elements of different cultures, and today the descendants of the inhabitants of the Nagaibak fortress are open to innovation. Thus, the Nagaibaks implement their natural mobility through extraordinary projects, such as “From Parizh to Paris: Traveling on the Ancestral Paths,” when, in honor of the 200th anniversary of the Patriotic War of 1812, the Nagaibaks visited European cities. The Nagaibaks’ trip was somewhat reminiscent of a pilgrimage, as they visited sites of military glory of their distant Cossack ancestors.

Nagaibaks actively engage in cyber culture, focused on festival movements and ethnic tourism. They enthusiastically reach out to those who are interested in their culture. They act in films dedicated to their traditions and help ethnographers who study their ethnicity and history. Activists present their culture at contests and festivals, mainly through folklore, clothing, language, and food.

At the same time, Nagaibaks are conservative about kinship. Any transformation of ancient customs and rituals is perceived as undermining the foundations of their ancestors. For example, they repeatedly denied reporters access to the filming of the traditional eulogy of Ash Bireu, explaining this by the need to preserve the “sanctity” of the event and to restrict participation to “close relatives.” In this regard, the Nagaibaks remain a closed people. The only condition for joining their group is through kinship.

Picture 5

Ash Bireu eulogy. Photo by E. A. Mikhaleva. Popovo

Friendliness-rivalry. The Nagaibaks formed their own “diplomatic” strategies of interaction with neighboring ethnic groups. On the one hand, the Nagaibaks admit affinity with other peoples. From their perspective, they are related by kinship with the Nogais, Arabs, Turks, Gagauz, and others. On the other hand, Nagaibaks see neighboring national groups as competitors or rivals. Some Russians and Tatars speak about the difficulties of living in Nagaibak villages. Oftentimes people cannot reconcile themselves with “Nagaibak envy,” “closeness,” and “unwillingness to admit strangers.” According to the Nagaibaks, a newcomer is immediately perceived as a rival: “Nagaibaks, especially in Ostrolenka, do not like poor people. If the person is quiet and calm, then he is a moron; if he is tenacious, then he is a beast.” School principal Egor Isupov noted a special “Nagaibak nationalism.” He commented: “Russians are perceived as simple Ivans: kind-hearted, open, and dull. The Nagaibak people are more cunning and secretive. On Nagaibak territory, Russians compete rather weakly with the Nagaibaks. Russians are perceived as people who can be used to make profit.”[18]

At the same time, the Nagaibaks emphasize their diplomacy in communicating with neighboring peoples. In their view, over the years of cohabitation, they have learned to interact with Russians, Kazakhs, Tatars, Bashkirs, and Kalmyks. Natalia Iuskina remarked: “We have no hostility towards other peoples. We love Russians equally, we love Kazakhs and Tatars alike. If all the peoples of the world were like the Nagaibaks, then there would be no war.”[19] Having lived most of her life among the Nagaibaks, Raisa Sidorina, who is Russian by nationality, managed to look at their culture from the outside:

To live on the border, you need to be very wise, and I believe that Nagaibaks are very wise. They can interact with Kazakhs, Bashkirs, and Russians, and at the same time be a closed community. They have normal tolerant relations with everyone because the border does not allow anything else. [20]

Conclusion

The Nagaibak ethnicity formed through external influences. Initially the tsarist government “formed” this group, creating the Nagaibak fortress with certain living conditions in it. Subsequently, leaders in Orenburg province transformed the identity of the Cossack group through its relocation to the New Line. Competition among Orthodox and Muslim missionaries in the late nineteenth through early twentieth centuries reinforced the differences between the three Nagaibak groups. The Soviet government made an attempt to replace Nagaibak with Tatar ethnicity. Yet thanks to the work of Mamet’ev, in the 1980s Nagaibaks independently mobilized and revitalized their ethnicity for the first time in a long while.

Isolation after resettlement, membership in a military class, and proximity to peoples of different traditions and beliefs, helped the Nagaibaks to become a “people of the border.” The borderland allowed the Nagaibaks to unite opposing currents in their ethnicity: hospitality and rivalry, and openness to innovations and closed traditions. At the same time, kinship in rituals and everyday life feeds the traditional culture of Nagaibaks. The multiethnic zone formed the Nagaibak people, which proved themselves adaptive to a multitude of changes. Due to the borderline status of their culture, in different periods of history, the Nagaibaks “activated” either openness or closeness, or various combinations thereof. If, according to R. Benedict (1934, 54), ethnic groups are divided into two types—“extrovert” (open and passionate) and “introvert” (closed and restrained), then with respect to Nagaibaks this metaphorical dichotomy is applicable in a situational context. Depending on time and circumstances, Nagaibaks preferred an open or closed style of self-positioning. The emphasis on closeness made it possible to preserve their culture in Soviet times (“introversion”). In the post-Soviet period, on the contrary, they mobilized their ethnicity through openness (“extroversion”).

This ethnic dynamism led to the transition of Nagaibaks from spatial mobility in the past to ethnic activation in modern times. Located at the crossroads of cultures—nomadic and settled, Christian and Muslim, European and Asian—the Nagaibak culture became receptive and adaptive. The nomadic and borderland Cossack sociocultural heritage served as the basis for the mobility and maneuverability of the Nagaibaks.

Translated from Russian by Alexander M. Amatov

References

Atnagulov, I. R. 2015. Identichnosti nagaibakov: genezis, struktura, dinamika [Identities of the Nagaibaks: Genesis, Structure, Dynamics]. Magnitogorsk: Magnitogorskii dom pechati. (In Russian)

Barth, F. 2006. Etnicheskie gruppy i sotsial’nye granitsy: Sotsial’naia organizatsia kul’turnykh razlichii [Ethnic Groups and Social Boundaries: The Social Organization of Cultural Differences], 9–48. Moscow: Novoe izdatel`stvo. (In Russian)

Barth, F. 1969. Introduction in Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference, 9–38. Bergen: Universitetsforlaget; London: Allen & Unwin.

Bekteeva, E. A. 1902. “Nagaibaki (Kreshchenye tatary Orenburgskoi gubernii) [The Nagaibaks (Baptized Tatars of Orenburg Guberniia)].” Zhivaia starina: 165–181. (In Russian)

Belorussova, S. Iu. 2017. “Rodstvo v etnichnosti nagaibakov [Kinship in Ethnicity of the Nagaibaks].” Ural’skii istoricheskii vestnik 2: 88–95. (In Russian)

Belorussova, S. Iu. 2016. “Nagaibaki na perekrestke pravoslavnykh i musul’manskikh missii [Nagaibaki at the Intersection of Orthodox and Muslim Missions].” Religiovedenie 3: 43–53. (In Russian)

Benedict, R. 1959. Patterns of Culture. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Den, V. E. 1902. Naselenie Rossii po piatoi revizii [Population of Russia according to the Fifth Revision]. Moscow: Universitetskaia tipografiia. (In Russian)

Golovnev, A. V. 2018. “Kontseptualizatsiia mobil’nosti v antropologii i etnografii [Conceptualization of Mobility in Anthropology and Ethnography].” Ural’skii istoricheskii vestnik 3: 6–15. (In Russian)

Golovnev, A. V. 2015. Fenomen kolonizatsii [The Phenomenon of Colonization]. Ekaterinburg: UrO RAN. (In Russian)

Golovnev, A. V. 2013. “Ural’skie etnodialogi [The Ural Ethnic Dialogues].” Ural’skii istoricheskii vestnik 2: 4–15. (In Russian)

Golovnev, A. V. 2012. “Etnichnost’: ustoichivost’ i izmenchivost’ (opyt Severa) [Ethnicity: Sustainability and Variability (Experience of the North)].” Etnograficheskoe obozrenie 2: 11–12. (In Russian)

Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive. Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London; New York: Routledge.

Leed, E. 1991. The Mind of the Traveler. From Gilgamesh to Modern Tourism. New York.

Materialy po istorii Rossii. Sbornik ukazov i drugikh dokumentov, kasaiushchikhsia upravlenia i ustroistva Orenburgskogo kraia. 1735 i 1736 gg [Materials on the History of Russia. A Collection of Orders and Other Documents Concerning the Rule and Government in the Orenburg Province]. Vol. 2. Orenburg, 1900.

Ratzel, F. 1882. Anthropogeographie. I Teil. Grundzüge der Anwendung der Erdkunde auf die Geschichte. II Teil. Die geographische Verteilung der Menschen. Stuttgart.

Rychkov, N. P. 1770. Zhurnal ili dnevnye zapiski kapitana Rychkova po provintsiiam Rossiiskogo gosudarstva, 1769 i 1760 godu [The Captain Rychkov’s Magazine or Daily Notes about Provinces of Russian State]. Saint Petersburg: Imperatorskaia Akademiia Nauk. (In Russian)

Rychkov, P. I. 1762. Topografiia Orenburgskaia, to est: obstoiatel’noe opisanie Orenburgskoi gubernii, sochinennoe kolezhskim sovetnikom i Imperatorskoi Akademii nauk korrespondentom Petrom Rychkovym [Orenburg Topography: Detailed Description of Orenburg County Written by Petr Rychkov, Collegium Advisor and Correspondent of Academy of Sciences]. Part 1. Saint Petersburg: Imperatorskaia Akademiia Nauk. (In Russian)v

Rychkov, P. I. 1762. Topografiia Orenburgskaia, to est: obstoiatel’noe opisanie Orenburgskoi gubernii, sochinennoe kolezhskim sovetnikom i Imperatorskoi Akademii nauk korrespondentom Petrom Rychkovym [Orenburg Topography: Detailed Description of Orenburg County Written by Petr Rychkov, Collegium Advisor and Correspondent of Academy of Sciences]. Part 2. Saint Petersburg: Imperatorskaia Akademiia Nauk. (In Russian)

Sofronov, M. 1898. “Religioznoe sostoianie nagaibakov prikhoda Fershampenuazskogo [Religious Condition of the Nagaibaks of the Fershampenuaz Parish].” Orenburgskie eparkhialnye vedomosti 21: 835–841. (In Russian)

Solov’ev, S. M. 1988. Sochineniia. Istoriia Rossii s drevneishikh vremen [Writings. History of Russia from Antiquity]. Vol. 1. Moscow: Mysl’. (In Russian)

Starikov, F. M. 1884. Otkuda vzialis’ kazaki (istoricheskii ocherk) [The Emergence of the Cossacks (An Historical Essay)]. Orenburg: Tip-lit. I. I. Evfimovskogo-Mirovitskogo. (In Russian)

Vitevskii, V. N. 1882. “Nagaibaki Verkhneural’skogo uezda Orenburgskoi gubernii [The Nagaibaks of Verkhneural’sk District of Orenburg Guberniia].” Volzhsko-Kamskoe slovo 72, 74, 80, 138, 144. (In Russian)

Urry, J. 2012. Mobil’nosti [Mobilities]. Translated from English by A. V. Lazarev. Moscow: Praksis. (In Russian)

About the author

Svetlana Iu. Belorussova—Candidate of Science in History, researcher in the Department of Ethnography of Central Asia, Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences; Associate Professor at Higher School of Economics (St. Petersburg campus).

*This study was funded by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR), research project No. 17-06-00119. The Russian version of this article was published: Belorussova, S. Iu. “Sostoianie pogranich`ia v nagaibakskoi etnoistorii, kul`ture i rodstve.” Tractus Aevorum 6 (1). Spring/Summer 2019: 17–41. ↩

1. “The Decree of Empress Anna Ioannovna to Rumiantsev and Kirillov.” In Materialy po istorii Rossii. Sbornik ukazov i drugikh dokumentov, kasaiushchikhsia upravlenia i ustroistva Orenburgskogo kraia. 1735 i 1736 gg. [Materials on the History of Russia. A Collection of Orders and Other Documents Concerning the Rule and Government in the Orenburg Province. 1735–36]. Vol. 2. Orenburg, 1900. P. 193. ↩

2. Den 1902, 211.↩

3. Starikov 1884, 177.↩

4. Atnagukov 2015, 39.↩

5. Rychkov 1762, part 2, 207.↩

6. Iskhakov 2004, 141–142.↩

7. Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv Orenburgskoi oblasti (State Archive of the Orenburg Region). Fond 6. Opis` 15. Tom 1085. List 4 oborot.↩

8. Field materials of the author (henceforth—FMA), Fershampenuaz, July 2014.↩

9. Nagaibaks consider Parent Days and Trinity as funeral customs associated with visiting cemeteries and having meals to honor the dead. ↩

10. FMA, Fershampenuaz, August 2015.↩

11. FMA, Ostrolenskii, August 2012.↩

12. FMA, Popovo, June 2014.↩

13. FMA, Ostrolenskii, October 2015.↩

14. Nagaibak regional television, Nedelia, November 11, 2011.↩

15. FMA, Ostrolenskii, August 2012.↩

16. FMA, Ostrolenskii, November 2015.↩

17. FMA, Fershampenuaz, August 2012.↩

18. FMA, Ostrolenskii, August 2012.↩

19. FMA, Ostrolenskii, August 2015.↩

20. FMA, Fershampenuaz, June 2014↩

This article was:

received on February 2, 2019

received after minor revision on April 10, 2019

accepted for publication on April 10, 2019

published online in Russian on August 7, 2019

published online in English translation on December 14, 2019